John McNairn 1910 -2009.

introduction to Bourne Fine Art exhibition in 2009 – Philip Long – then senior curator Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art.

John McNairn’s art and career is a treasure to be uncovered and explored. His longevity (McNairn is now in his 99th year) allows direct insight into the concerns of a Scottish artist in the first half of the last century, as well as to professional opportunities then available. His art is not well known compared with close contemporaries such as William Gillies and William Mactaggart, but like them he made the Scottish landscape a subject for sensitive and insightful scrutiny, and an acquaintance with his work brings fresh pleasure to our understanding and knowledge of the native art of this country.

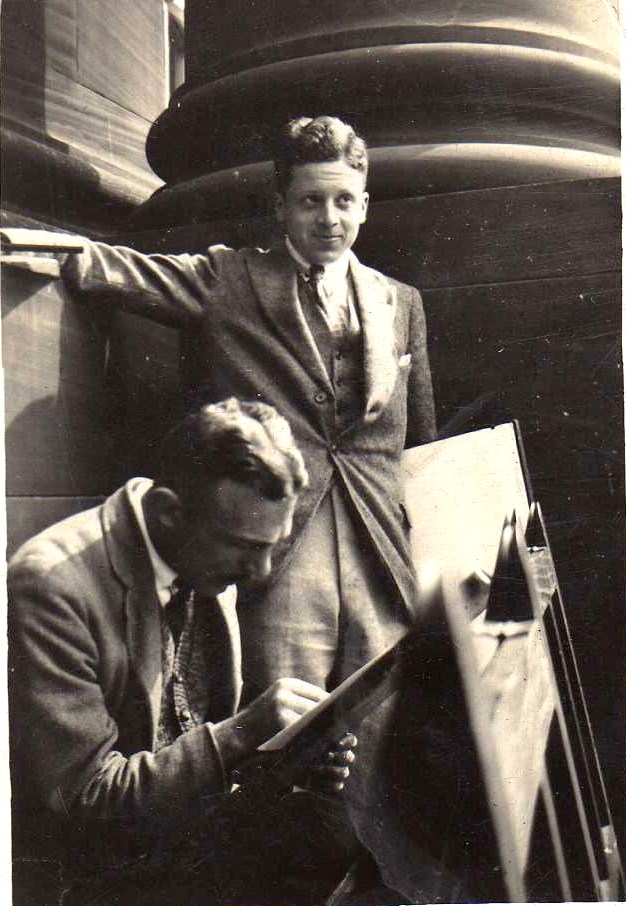

Born in 1910 in Hawick, an early childhood recollection of McNairn’s (during a visit to Kirkcaldy) was the ominous sound of the nary firing on the Forth in practise for the War, an event of important personal significance, as it coincided with his father’s voluntary enlistment. John McNairn senior (1881-1946) ran the family-owned Hawick News, and was also a serious and progressive amateur painter, who found inspiration in the letters of Van Gogh. He encouraged his son to enrol at Edinburgh College of Art, where McNairn began in 1927 at an especially fertile period in the college’s history, re-energised after the war years by returning and new students. Although McNairn recollects an initial awkwardness (which he attributes to his country background), he quickly came to admire William Gillies and in particular the teaching of D. M. Sutherland. Both tutors had studies on the Continent (the younger Gillies only recently, in the cubist André Lhote’s Paris studio), and McNairn followed the custom for the most talented Edinburgh students to go to London and then, on graduation, to go abroad to continue their development.

In Paris in the early 1930s McNairn made, at least among Scottish students, the unusual choice of attending the Academie Scandinave, attracted by the presence of Othon Friesz. Although Friesz no longer painted in the vigorous Fauve style of his early career, his connection with Post-Impressionism appealed to McNairn who expressed a wish to paint in a direct and truthful manner. McNairn has also related that his interest in the academy was through its historical association with Edvard Munch, whose late landscape work had been exhibited to such powerful effect in Edinburgh in 1931. Munch’s art had an immediate influence on Scottish painters, such as MacTaggart and Gillies, who began to explore their native surroundings with a less controlled, more expressive approach, which, it was argued, was right for northern climes and a northern artistic temperament. This might be said to characterise McNairn’s subsequent art, but for a while in Paris exposure to further progressive trends opened his eyes to other possibilities. Through his friendship with Robin John (son of Augustus John) he was introduced to Julian Trevelyan and S.W. Hayter, whose print studio, Atelier 17 was used by the most prominent artists, including many of the leading Surrealists. With Trevelyan, he saw the Surrealists’ 1933 Paris exhibition and recollects the disturbing effect Dali and Miro had on him. Consequent paintings such as The Harbour, Ely have an unsettling emptiness, accentuated by McNairn’s central treatment and slightly unreal perspective of the loose timbers, that recalls the work of his English contemporary Tristram Hillier, who too was exposed to Surrealism in Paris in the earl 1930s, and whose precisely observed scenes invariable have an otherworldly surreal edge.

Following his return to Scotland, McNairn was given his first teaching job at West Calder High School, before being called up to train as an aircraft inspector. After war service in India, he returned to West Calder where he met his future wife Stella. The newly weds then moved to Hawick and then to Selkirk, where John became Head of the Art Department at Selkirk High School. Shortly afterwards they moved to a cottage in the nearby village of Midlem, where they were neighbours to sculptor Alexander Carrick, who fostered the McNairns’ interest in Scottish architecture, furniture and craft. In 1970 they bought a Georgian house, Broomhill, on the edge of Selkirk, which McNairn had admired from his school window and which he and Stella gradually and lovingly restored. Broomhill provided an ideal setting for both the art and their collection of textiles and furniture, which included a cabinet hand-painted by Anne Redpath, whom McNairn had known as a Hawick family friend. Here, they raised four children, including the talented artists Caroline (b1955) and Julia(b1962) who too studied at Edinburgh College of Art.

After the move to Broomhill, the surrounding gardens became a fertile subject for McNairn’s paintings when time allowed away from teaching and family commitment. As the works in the exhibition show, the surrounding Borders countryside dominated in the years before this move, especially the bold forms of the Eildon Hills and the beauty of the Ettrick Valley. McNairn’s preference has always been to paint directly from his subject, both in oil and in watercolour, the latter utilising a strong graphic line, ornamented by pale washes of colour; the oils, such as The Ettrick Valley in Winter, of 1967, have a boldness and uncluttered simplicity which reflect the practical consequences of working in this medium, frequently on a large scale, out-of-doors. McNairn’s oeuvre suggests his preference has been to work from the Borders countryside under flat light or during exposed colder times. Oils such as Brown Landscape tell of the artist’s interest in the natural structure and earthy colouring of his local environment revealed under these conditions. A brighter palette is reserved for places visited on holiday, the Galloway fishing village Portpatrick and Eyemouth on the east coast, depicted en fete. In this, McNairn inventively used the device of fluttering coloured flags to trace a rhythm across the centre of the composition, which has all the joy seen in the bright world of artist Raoul Dufy, who had been a friend of Friesz and whose work McNairn continues to admire.

McNairn’s painting has been infrequently exhibited. In 1950, Edinburgh’s The Scottish Gallery held a joint exhibition of McNairn and his father’s paintings (shorly after the latter’s death), when it was noted the younger artist had inherited his father’s love of colour. This celebration of a family’s art was repeated in greater form, when five generations of McNairn artists were brought together in an exhibition in Peebles in 1987. Between these years, McNairn was frequently included in other exhibitions, and he organised displays of his own in the gallery he and his wife established in Selkirk. Occasionally he submitted work to the Royal Scottish Academy , but found it was not always accepted. He has politely observed that there has been no place in his art for invented subject matter as a means to make virtuosic statements in paint, and this may be why his work did not always find favour. Throughout his admirably long career McNairn has steadfastly produced paintings in which he as fastidiously orchestrated a simple vocabulary of forms, line and colour, to produce and art that encapsulates the inspiration he has clearly felt in his observation of the world around him. We should relish this opportunity to see in concentration his distinguished painting.

John McNairn died in 2009 shortly after this very successful exhibition happened. Arty had been the nickname given him by his pupils at Selkirk High. There was always a tension and still is between being a teacher and an artist. Can you be both? This site is called Arty in memory of John McNairn 1910-2009, teacher and artist, artist and teacher.