The Scottish Borders – homeland

The Roman Occupation of Britain was never completed. A fortified wall had to be built across the Island because the Romans, despite several attempts, failed to subdue the British tribes in the North. This wall, named after emperor Hadrian, was manned and defended for 300 years. The land between the wall and the Firth of Forth which includes the region now known as the Scottish Borders was inhabited by a people known to the Romans as the Votadini, a British tribe who cooperated with Rome to the extent that the Romans allowed them to continue to bear arms, unlike other British tribes, who had been disarmed under the occupation. The Votadini helped the Romans defend their Northern frontier against raiders from further North. They were horse people and the Romans helped to train them in cavalry tactics of warfare.

When the Roman legions left Britain in around 400AD, there was a power vacuum in the country which allowed the advance of Germanic speaking Anglo-Saxon settlers from the east. Border author Alistair Moffat has researched this period and believes that the Vododini/Goddodin people of this region were able to hold back the Anglo Saxon invaders for a considerable period of time, slowing their advance into what is now Scotland. In fact, Moffat believes that the Arthur legend actually relates to this resistance struggle and that Arthur was in fact a Goddodin/Votadini military leader, skilled in the use of cavalry in warfare.

The Goddodin resistance was eventually overcome and the Anglo Saxons were able to move into Southern Scotland. This is documented in one of the earliest Celtic texts, found in Wales, written by the warrior poet Aneurin who was one of the few to survive a final battle which took place between the Goddodin and the Anglo Saxons. There is a romantic idea in the McNairn family that the name McNairn originated from the followers/descendants of Aneurin, who were driven to the South West of Scotland after their defeat. Certainly the name is common in the South West, in Galloway, and artist John McNairn’s grandfather, also John McNairn, and also an artist, was born there.

Of course, the Welsh language of the Goddodin is long gone from the area but the people are still strongly independently minded, and have retained the love of horses and riding.

During the centuries when Scotland and England were frequently at war, the area became effectively a buffer state between the two kingdoms, dominated by a warlord society, and dotted with fortified houses. Riding was a way of life and, couple with raiding, also a means of subsistence.

Following the Union of the Crowns in 1603, the Borders were forcibly and sometimes brutally pacified, becoming gradually assimilated into Scotland proper although still to this day the people are distinct in their culture and manners from the lowland Scot.

William Johnstone, and Anne Redpath are two other artists who were from this Borderland and each of these, like John McNairn, owed a debt to the land, its landscape and tradition. John knew both of these artists and Anne gave him and Stella a painting for their wedding in 1948. Anne also painted a portrait of Stella. William Johnstone was brought up on a farm very near Broomhill in Selkirk and returned to farming after his celebrated career both as artist and leading British art educator.

Hawick

Hawick was John McNairn’s birthplace and his home town. It is one of the largest towns in the Borders and when John was young it was a prosperous Textile town, specialising in knitwear.

The origins of the town of Hawick are unclear but it is situated in the classic defensive position of a confluence of two rivers. In Hawick’s case these are the Slitrig and the Teviot. In the reign of King David of Scotland, 1124 – 1153, a motte and bailey was built, which was a classic Norman structure, both defensive and for living quarters. The motte survives and in Hawick is now known as ‘the Moat.’ Whether there was a settlement there before it became known as Hawick is unclear. Hawick is an Old English name and clearly given to the place by the invading Angles as they moved eastwards after the Roman occupation. The old idea that the Angles displaced all or most of the native Celts is now outdated. While it is true that the Brittonic language disappeared apart from in Wales, a language and a culture can become dominant without replacing the indigenous people. We can see echoes of the Celtic culture in folk traditions and beliefs as well as in music. The horsemanship tradition of the Goddodin people also continued and is celebrated today in the Common Riding tradition of the Border towns.

Hawick was never made a Royal Burgh and was a small Border town until around 1770 when knitwear manufacturing started and a growth in both population and prosperity which lasted right up to the mid 20 century. With the construction of a railway to Carlisle and onwards to London the town was able to export its quality knitwear to England and Europe and in the 1960s the town was reputed to have the highest per capita income of any town in the UK.

John McNairn’s father, also John McNairn, was the owner of the Hawick News and loved to paint – in watercolour. His early watercolours were subdued in palette and traditional in character but after reading Van Gogh’s letters he was inspired to express himself more simply and intensely, still in watercolour. He always used the highest quality watercolour paper and paint and was not remotely interested in exhibiting or selling his work. He painted simply for the pleasure it gave him, being outside and capturing what he saw and felt in paint. They weren’t painted for the Hawick Art Club to put it another way. He had a deep interest in spirituality of the Theosophist school.

Edinburgh

John liked to draw and paint from a young age and was encouraged by his parents and school to go to Edinburgh College of Art. He did well enough at college to win a travelling scholarship to Paris and Spain in 1932. John credits his time in Paris as a turning point for him where he started to free himself from what his teacher in Paris described as ‘illustrative’ technique. He remembers Othon Friesz, who was one of the original Fauve painters complementing him on his change in direction – ‘Vous avez cherché la forme.’. On his return to Scotland he brought this new sensibility to his painting and drawing as he started a career as a teacher, first of all in West Calder High School where he taught until the outbreak of war. All through this period he painted and with some success in terms of paintings being selected by the SSA and RSA for exhibition and favourably reviewed. After War Service with the RAF in India he returned to West Calder and met one of his former pupils Stella Gibson. They got engaged and married. Stella trained as a sewing teacher and she also loved to paint. She painted and exhibited in watercolour with some recognition. Her paintings are modest in scale and gentle in manner. Her younger sister Doreen, also taught by McNairn at West Calder, became the Tanzanian artist Doreen Mandawa.

Midlem

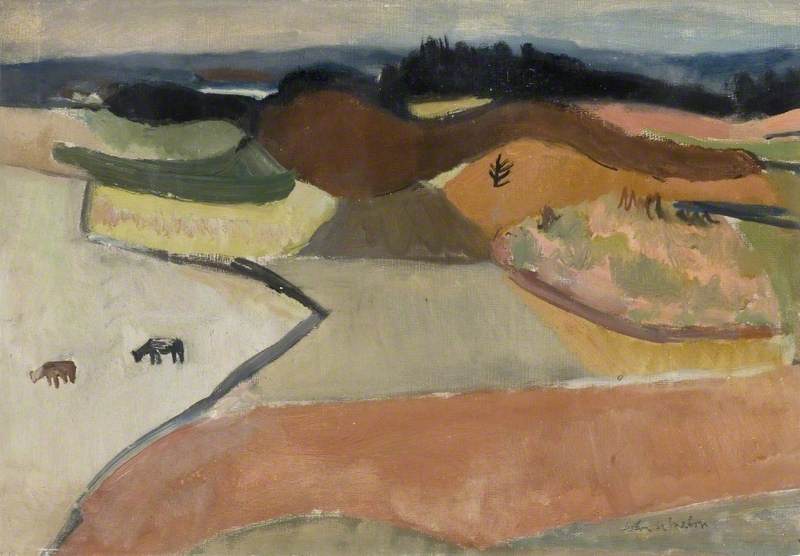

After the war, John and Stella married and briefly lived in Hawick before John became the principal Art teacher at Selkirk High School. They moved to Selkirk, where their first child, John, was born. Soon after, they relocated to the small village of Midlem, about four miles south of Selkirk. The village lies at the start of the southern slope leading to the English Border and the Cheviot Hills. It features a large village green surrounded by cottages, each with a strip of land at the back. Historically, this settlement system dates back to medieval and Anglo-Saxon times, with narrow strips of land behind the houses cultivated in rotation rather than owned by individual cottages. The McNairns lived in Midlem for five years, during which their second child, Douglas, was born. Here are some paintings from that period:

Selkirk

Selkirk is 12 miles from Hawick and similar in many respects. The old town is built on a hill on the south side of the River Ettrick about 4 miles above where it joins the Tweed. In 1955 the McNairn family moved from the village of Midlem into a house which had been at one time a big Victorian mill-owners property called Bridge Park, with a drive, a large field stretching down the hillside and a tennis court. All overgrown and a bit neglected when the McNairns bought the house. They demolished a two storey section to make it more suitable in size for the family. Bridge Park faced westward with a view up the two valleys of Ettrick and Yarrow and the high hills beyond, at the watershed of Southern Scotland.

Two daughters were born during the family’s time at Bridge Park, Caroline, born in 1955, and Julia, in 1962.

Broomhill

Broomhill is an eighteenth century house originally built as a dowager house for the Sunderland Hall Estate and added to in the late eighteenth century with two storey front and back extensions. It was again extended in the 1920s with a single storey addition.

In front of the house is a walled garden and a lawn sweeping down to a wooded dean (the Hurlin Dean).

The town of Selkirk is visible through the trees and beyond it the hills of the Ettrick and Yarrow valleys.

John McNairn could see the house from his Art Room at Selkirk High School and it was a kind of dream for him to live there which became real when the house came on the market in 1970.

It was a bit run down and had some problems arising from the various extensions to the original house which had been beautiful but small in scale. These extensions had made the core of the house dark and with complicated corridors so the McNairns opened it out front to back, connecting the front room with the rest of the house.

During his time at Broomhill, McNairn’s art became focussed very much on the house and garden in terms of subject. It got lighter in touch and more minimal. Letting light and white in, just as he and Stella had done with the house.

In the 1950s, Broomhill had been the home of the Selkirk doctor David Graham who was the son of John Anderson Graham of Kalimpong, North India. David’s sister Betty was married to the celebrated Plant Collector George Sheriff. The garden, although neglected, still reflected this Himalayan connection when the McNairns moved in, with a bed of the blue meconopsis and other plants from the region. They found a stone Buddha, on its side with the head snapped off, which they restored and set beside the small pond in the middle of the walled garden. This Buddha became a still point and a focus in many of McNairn’s later oil paintings, watercolours and drawings.